Lal Shahbaz Qalandar was a holy man and scholar born in the

1100s whose ancient travels sound as contemporary as today’s news feeds.

He was born in what is now Afghanistan; he was the descendant of

immigrating Iraqis; he lived and died in Pakistan; and his shrine was

constructed by donations from the Iranian royalty.

Maybe the only thing more extraordinary than Lal Shahbaz’s

wide-reaching travels and popularity are the many mythological stories

that have been attached to him over the centuries. In one story,

recorded by William Dalrymple, Lal Shabaz was wandering

through the desert with a friend as evening began to fall. The desert

was terribly cold, so the two pilgrims began to gather wood for a fire.

With their pyre neatly constructed, they realized they had no

way of igniting it. Lal Shahbaz’s friend suggested that he transform

himself into a great bird (the meaning of “Shahbaz”) and fly down into

hell to collect coals for a fire. Lal Shahbaz considered this a wise

suggestion and flew away.

After many cold hours Lal Shahbaz returned to his friend

empty-handed. Puzzled, he asked why he had not returned with fire to

keep them warm. Lal Shahbaz replied, “There is no fire in hell. Everyone

who goes there brings their own fire, their own pain, from this world.”

There is a great deal of truth in this story. If we think of

hell as a self-imposed prison or a self-ignited blaze, then Lal Shahbaz

is correct: Anyone suffering from the results of their own hard-hearted

decisions or their own hand is truly suffering hell. They have not been

cast away by God; they have kindled their own fire. They have hurt

themselves, and nothing hurts worse than a self-inflicted wound.

By Jesus’ definition, the most “burning torture to bear” is the

scorching heat of resentment and unforgiveness. When we refuse to

forgive others, we sentence ourselves and our world to hellish

suffering. Our future — and today’s well-being — depends upon our

willingness to extinguish the burning inferno in our souls by forgiving

those who have harmed us.

Granted, we don’t naturally respond to injustice with this kind

of Christ-infused grace. If you hit me, I will hit you harder. Maim my

brother, and I will kill your father. Set off a bomb in my marketplace,

and I will wipe out your entire village. Firebomb my hospital, and I

will bomb your capital.

It’s human nature to retaliate, not with equity, but with

greater force than what was first inflicted. It is a hellacious, vicious

cycle; and the only thing that can shut down the scorching cycles of

suffering is forgiveness.

Dr. Fred Luskin offers this hopeful counsel: “To forgive is to

give up all hope for a better past … Forgiveness allows you a fresh

start … It's like a rain coming to a polluted environment. It clears

things. At some point, you can say that this awful thing happened to me.

It hurt like hell, yet I'm not going to allow it to take over my life.”

Forgiveness forges a firebreak and says, “It ends here!”

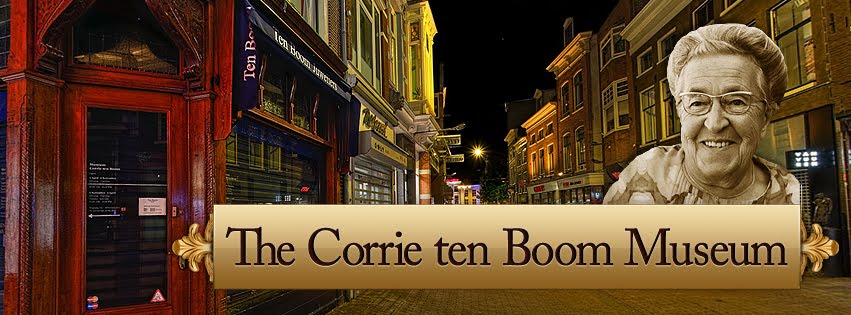

So when we hear the names of Auschwitz and Ravensbruck, we

answer with the names of Maximilian Kolbe, Corrie Ten Boom, and Bernard

Lichtenberg — people who were not overcome by evil, but overcame evil

with good.

When someone speaks of the past or current hatefulness in South

Africa, Darfur, Armenia, Sand Creek, Selma, or Croatia we speak the

names of Desmond Tutu, Martin Luther King, Jr., Mother Teresa, Miroslav

Volf, Dirk Willems, and the Amish of Nickel Mines – those who lived (and

some died) for the sake of grace.

The only way to stop the continual and rampant hate in this

world is to make peace. The only way to make peace is to forgive. The

only way to forgive is through the unrelenting love and forgiveness of

God. We can become the instruments of that peace, tools of God’s

forgiveness, and the images of God’s love. That love will extinguish the

fires of hell. That love will indeed change the world.

Source: Waltonsun